In the 2010s, affiliate marketing became a dominant strain of online business models. The Wirecutter, which sold to the Times in 2016, made money by driving its visitors to retail Web sites like Amazon or Best Buy, taking a small cut from any purchase of items it recommended. In 2017, New York relaunched its own buying-guide section, the Strategist, as a standalone site. In its posts, journalists and celebrities explained which toothbrushes, suitcases, or couches they liked; the revenue from such product referrals was part of why Vox Media acquired New York in 2019. Since then, online recommendations have crept ever further into the media ecosystem. Platforms want to tell us what to buy, where to eat, and, generally, how to live better consumerist lives. TikTok shopping videos occupy increasing real estate in users’ feeds, with aspiring influencers shilling beauty products, cooking tools, or athleisure gear whose benefits they personally espouse with the energy of QVC pitchmen. Letterboxd, a social network focussed on movie reviews, promises to solve the conundrum of what to watch by having users rate what they’ve seen so that others can follow: “Tell your friends what’s good,” the site’s slogan runs. Beli, another app, helps you “track and share your favorite restaurants.” E-mail newsletters encourage a kind of benign narcissism: in the quest to fill readers’ inboxes, authors resort to sharing the latest books they’ve read, albums they’ve listened to, and podcasts whose opinions they’ve adopted.

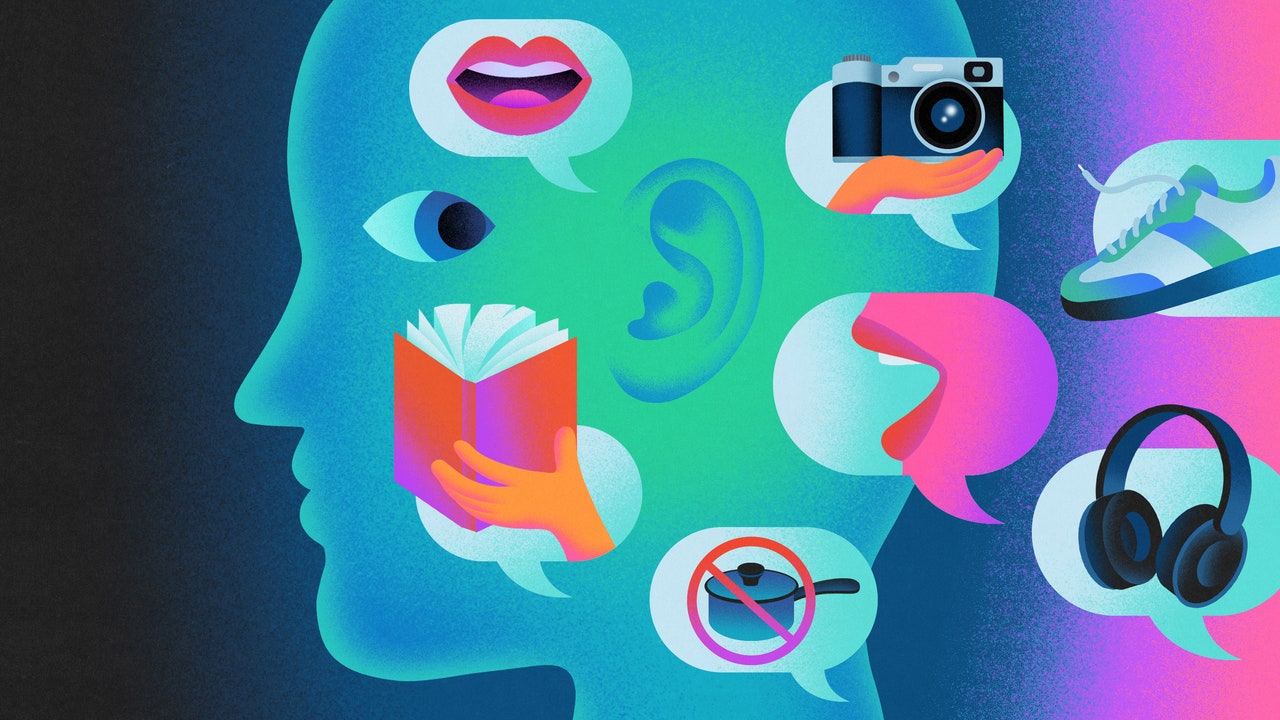

This recent surge of human-curated guidance is both a reaction against and an extension of the tyranny of algorithmic recommendations, which in the course of the past decade have taken over our digital platforms. Today’s automated social-media feeds deliver increasingly indistinguishable content now sometimes generated by artificial intelligence; in the face of this onslaught, we crave content with evidence that a real person actually stands behind the products or works being touted. Since the late 2010s, publications have run clickbaity guides in the genre of “Ten Things to Watch on Netflix Right Now,” but the genre of personal recommendations became entrenched during the pandemic, when the biggest problem besides avoiding COVID-19 was deciding what to watch next on TV. At the same time, social media was entering a more multimedia phase, with podcast audio and TikTok video highlighting voices and faces, building a new generation of micro personality cults. If you follow someone’s life voyeuristically online, you might want to know what they recommend eating for breakfast or wearing to bed.

One outlet emblematic of the new recommendations cottage industry is Perfectly Imperfect, a newsletter founded in 2020 by Tyler Bainbridge, a software engineer at Facebook. Twice each week, subscribers receive a list of recommendations from young musicians, artists, or Internet celebrities on everything from niche cultural products to run-of-the-mill self-care accessories. Molly Ringwald recommended the Criterion Channel. The songwriter MJ Lenderman recommended “Shoes w no laces.” Jack Antonoff recommended saline nasal spray. Each recommended item is published with a relevant emoji and explained with a brief blurb of text. The newsletter is designed, as Bainbridge told me recently, “to break you out of your algorithm by just showing you what someone else likes.”

In March of 2021, Bainbridge moved to New York City from Boston and drew subjects from the nascent cultural scene around Dimes Square, the downtown neighborhood that became a destination during quarantine. “When Catholicism and religion was getting trendy downtown, you can see that in the recommendations. We have much less of that now,” he said. (The downtown writer Matthew Davis did recently recommend praying the Rosary, though he acknowledged that it was not a fresh tip: “people have been doing it for like 1000 years.”) In May of 2023, freshly laid off from Facebook, Bainbridge decided to take the project full time. The newsletter’s combination of pithy irreverence and countercultural credibility had proved popular and grew more so, accumulating nearly five hundred subjects. Bainbridge also built a separate Perfectly Imperfect social network where users could post their own unedited recommendations and read those of others. As of this month, Perfectly Imperfect is graduating from Substack to its own self-contained Web site (designed in lo-fi Geocities style by the same firm as the campaign for Charli XCX’s “Brat” album) and beginning to produce videos. The relaunch featured a post by Olivia Rodrigo–the most famous participant to date–recommending English breakfast tea and a card game called Kings Corner. The site so far has nearly a hundred thousand users. Bainbridge told me, “P.I’.s goal is to be kind of the universal place for taste.” (He has recommended nearly fifteen hundred things on his own account, ranging from the New York restaurant Congee Village to “being sincere.”)

The word “taste” has lately become a bugbear of the tech community. Recommendations online are ubiquitous—we have posted our likes on the Internet since the earliest days of Facebook profiles—but “taste,” with its suggestion of deeper knowledge, perhaps, of why or how something is good, transforms the act of recommending into something specialized, with an aura of irreplaceability. In a recent essay, “Taste is Eating Silicon Valley,” the entrepreneur Anu Atluru attracted attention for her argument that taste was the new dominant commodity in an era of generative artificial intelligence, when knowing how to prompt a machine threatens to supersede human knowledge or skill. “In a world of scarcity, we treasure tools. In a world of abundance, we treasure taste,” Atluru wrote. Given that the Internet offers us so many options, the choice of what to pay attention to, what to consume, or even what to create matters most. By sharing your taste online, you can develop cultural capital. As Bainbridge put it, “Making the right recommendation comes with clout.”

Thus Internet denizens compete to make the best, most authoritative or provocative recommendations. A friend of mine, the newsletter writer Delia Cai, observed to me recently that the digital-media landscape often feels like “just a list of recommendations on where to get your recommendations.” Perfectly Imperfect in some ways attempts to resist the wanton commodification of online personality. The site doesn’t tally follower counts or promote content algorithmically; posting is done for the mere pleasure of sharing (or, at least, for the chance for your picks to be featured in the newsletter alongside a more famous person’s). Perhaps in part because of the absence of commercial motivation, the recommendations on P.I.’s site tend toward the pleasantly banal: “basking in the sun coming through the window like a cat,” “being radically honest with yourself,” the film “Practical Magic.” The content feels more like a hub of personal blogs or a selection of posts from early-2010s Tumblr. There are at least nine suggestions to call or visit your grandparents.

One problem with recommendations as the grist for the digital content mill is that there are only so many things to recommend. Repetition, or scalability, is the enemy of taste, because in time it reveals a latent sameness in what we all like to like. Bainbridge acknowledged the problem: “You want to feel unique and you want to feel like you have your own thing. The minute more people are talking about Bar Italia”—an indie London rock band—“or whatever, you feel like you’re less of an individual.” Sharing recommendations online now can present a quandary when it comes to spreading things you are deeply, personally passionate about: if the algorithmic content feeds get hold of it, it’s likely to be blasted to millions of people and erode your personal claim to whatever the thing is that you love. (Or worse, fed into the maw of generative A.I. and reproduced.) A restaurant grows insurmountably booked; a musician’s work gets churned through social-media discourse. It might be safer just to recommend nasal spray.

Plenty of recommendation culture remains focussed on efficiency. We want to consume the best things, develop the best habits, and visit the best places. And yet unchecked efficiency, whether algorithmically or organically promoted, is inhospitable to the development of a deeper sense of taste. Another buzzword—“gatekeeping”—has taken on a new and different valence online lately, to express a desire not to recommend. “Gatekeeping” means keeping insider information to yourself instead of tossing it to the winds of the Internet. In another much-discussed recent essay, the designer and artist Ruby Justice Thelot praised the gatekeeper for erecting “the fence which the enthusiast happily hops” but which “stops the dilettante”—in other words, for making it hard to experience whatever is being recommended without a bit of investment. Mundane things are easy fodder for recommendations; what is truly closest to your heart might warrant a bit of withholding, however antithetical it seems to the pressures of being online. ♦