In March 2009, just a few months after the 2008 stock market crash, Disney CEO Bob Iger gathered company shareholders inside Oakland’s Paramount Theatre, a short drive from Pixar’s headquarters in Emeryville. “We are meeting during perhaps the most difficult economic times of our lifetime. And these are conditions that even the strongest companies can’t fully escape,” Iger told the crowd. “I’m confident, though, that our brands, our products and our people can overcome the challenges ahead.”

Eventually, the economy recovered, and so did Disney. But that didn’t diminish the short-term discomfort. As damaging as that crash was, however, the media business had a strong foundation to fall back on; 2008, in fact, represented the peak of pay TV, per Leichtman Research Group, with 87 percent of households, more than 100 million strong, paying their cable or satellite bills every month as entertainment giants reaped their share amid the pain.

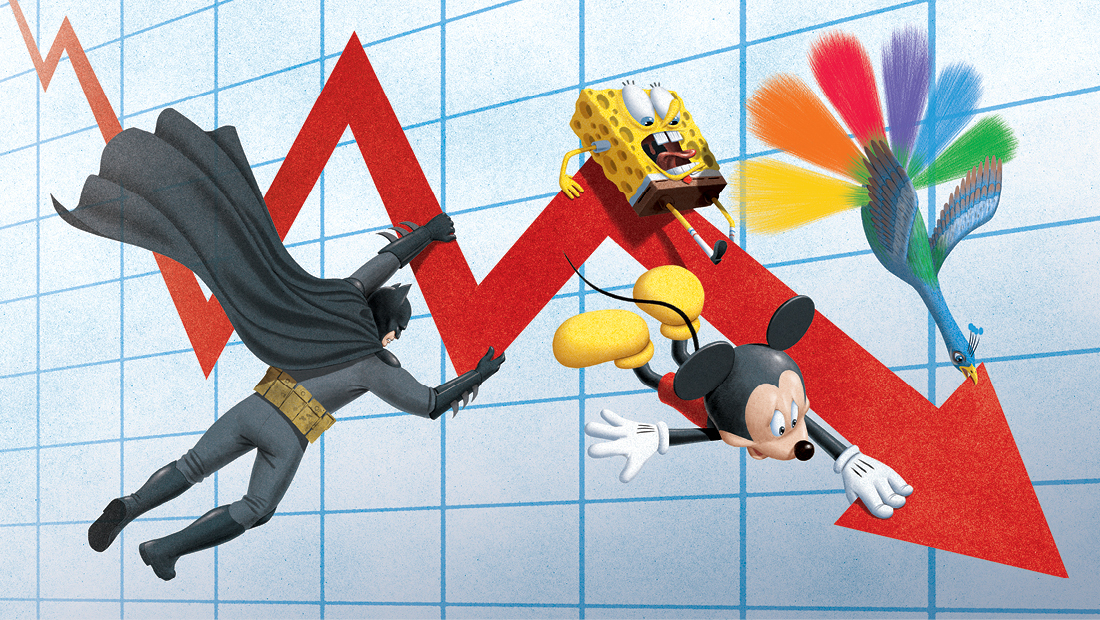

Now the economy feels as if it is again on a precipice, with a tariffs-induced shock stinging global markets. But this time, TV’s financial system is radically different. Disney is in many ways a textbook example. Yes, its advertising took a hit in 2008, as did its theme parks business, the result of consumers reexamining vacation plans. But ESPN saw growth, thanks to contractual rate increases and pay TV’s ubiquity.

Pay TV was a utility, something every household needed to have, like electricity and water. Now, it is a shell of its former self, with fewer than 70 million households and falling rapidly. Consumers get their entertainment, news and sports through a hodgepodge of streaming services, with some seen as necessities (maybe YouTube and Netflix) and others seen as expendable. And unlike cable TV, unsubscribing is as easy as clicking a button.

And while the 2020 pandemic shock worked to the benefit of legacy media entering the streaming fray (bolstered by consumers largely staying home), 2025 is a different beast, with inflationary concerns top of mind and no shortage of other entertainment options available.

In an April 10 report titled “never-ending tumult,” Bank of America analyst Jessica Reif Ehrlich noted that “traditionally, cable companies have tended to be viewed as defensive in recessions. This view has been driven by the utility and subscription-based nature of their offerings as well as limited competition against those offerings. However, Cable operators now face increased broadband/video competition vs. prior recessions. This backdrop challenges the traditional perception of Cable companies as safe havens during an economic downturn.”

Most know that advertising is always impacted in recessions, but there’s reason to believe that a recession this time could be worse than in downturns past. In 2008, TV was the king of advertising, accounting for the lion’s share of ad spend, according to Magna. Today’s advertising environment is vastly different, with tech giants Google, Meta and Amazon dominating the space with performance-driven ads as TV’s piece of the pie shrinks (though streaming and connected TV ads are growing, albeit not enough to offset linear’s losses).

A recession now could be the thing that pushes linear TV off the edge. “Given the ongoing secular headwinds facing the linear TV ecosystem, we worry that television could mirror the fate of radio and newspapers during past recessions,” MoffettNathanson’s Michael Nathanson wrote in an April 9 report, adding that $45 billion in ad revenue could be lost in a recessionary situation. “Should budgets shift away from linear TV at an accelerated pace, we see risk of a more permanent reallocation toward connected TV and broader digital channels.”

“We continue to believe that Online advertising will hold up better than traditional TV and other legacy channels,” he continued. “In a more cautious environment, marketers will prioritize performance-driven advertising over broad brand campaigns — a dynamic that favors digital and measurable media.”

Media analyst Brad Adgate was an executive at Horizon Media in 2008. He recalls the mass layoffs that the advertising and media businesses went through amid the tumult. “That’s what I remember most vividly,” he says, adding that he sees TV as particularly at risk in this moment. “There’s concern that if the budgets are going to remain flat or even drop, it’s going to be much more pressure on video and television to compete with all the choices marketers have.”

But even tech giants are exposed. Amazon CEO Andy Jassy was asked April 10 on CNBC if his company is feeling a pinch in its advertising business. “When you have things like tariffs, it’ll create macro issues where it depresses demand or drives inflation,” he noted.

At Warner Bros. Discovery, CEO David Zaslav sent a note to staffers telling them to batten down the hatches and reduce discretionary spending because of “market volatility and reduced consumer confidence.”

That said, TV still has an ace up its sleeve in the form of live sports — the NFL in particular. Its scale is unmatched, and advertisers are unlikely to meaningfully scale back their sports investments. Or as Reif-Ehrlich writes: Sports “remain resilient in tepid advertising markets.”

But even there, any benefit is splintered and offset. Disney benefits from sports thanks to ESPN, but its theme parks are extraordinarily exposed in a downturn. While Disney and NBCUniversal’s experiences business are brand-defining in most economies, in a recession, their high fixed costs become a burden, as consumers pare spending. Disney and NBCU also have historically benefitted from such consumer products as toys and clothing, where licensing deals mean fat margins for the IP owners. But given the steep tariffs on China and Vietnam, those margins are bring pressured. That said, Reif-Ehrlich notes the opening of Epic Universe could help NBCU manage some of those issues, given likely demand for the entirely new Orlando theme park.

Despite all the doom and gloom and the difficult comparison to past recessions, some analysts still see green shoots. The music business is vastly healthier than it was in 2008, when Spotify was still an experiment in Sweden, the record labels were reeling and Apple’s iTunes carried the day. Multiple analysts are framing Spotify and music industry stocks as a safe haven. “We very much doubt that a recession would drive a meaningful increase in churn at what are reasonably priced music subscription services,” TD Cowen’s Doug Creutz wrote April 9.

Similarly, Netflix is seen as “more resilient” than other entertainment companies, says Nathanson, given its dominance in subscription streaming and the fact that advertising is not yet a meaningful driver of its business, allowing it breathing room that more established media companies don’t have. Even there, of course, pressure remains. “Tougher macro/recession could delay [Netflix] price increases in certain markets,” JPMorgan’s Doug Anmuth noted on April 8.

And yet anxiety remains high, with tariffs and a recession not the only tail risks facing the industry. One media veteran says that entertainment executives they have spoken to are already gaming out scenarios where interest in American popular culture sours and the globalization of entertainment that has spread U.S. franchises and brands around the world begins to reverse in favor of more localized fare. That is a world where some of Hollywood’s greatest strengths — its decades of beloved IP — could work against it, and the ramifications of that new world order, should it come to pass, would be sweeping.

This story first appeared in the April 16 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.