This article is part of Give Us This Day: A Vittles London Bakery Project. To read the rest of the essays and guides in this project, please click here.

Tomorrow, look out for the definitive, subscriber-only, two-part London bakery guide out Friday!

The London sandwich timeline, by Hester van Hensbergen

Many of the greatest meals between two slices of bread never become trends. The sandwich is one of the most accessible forms of culinary invention, and some of London’s best might be those known to only a handful of people – something sparked by what was lying in the fridge one Sunday afternoon, eaten over the chopping board to a hum of surprised delight; an idea that stuck, a recipe never written down.

This timeline of iconic sandwiches doesn’t tell these stories. There are few home kitchens here, except for those written into the pages of a newspaper or recipe book. Instead, there are private members’ clubs, coffee shop franchises, and cooking shows. There are no quiet moments of private appreciation; these are sandwiches that announced themselves, generating queues and crowds and noise, from hollers in the streets to streams of hyper-colourful Instagram photos. This is a potted history, not of London’s greatest sandwiches over the last two-and-a-half centuries, but of the most iconic ones. The ones that gathered heat – usually through the exercise of cultural and economic power – and created a collective thrill across the city.

1762 – THE PRIVATE MEMBERS’ CLUB ONE

The ‘sandwich’ was a trend from the start, but not a genuine invention; using bread as a vessel for other food is literally one of the oldest tricks in the book. In the eighteenth century, you would’ve had to have lived an incredibly sheltered existence to find this way of eating novel, which is why it was John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, and his coterie of aristocratic friends who got to name it. The Earl’s habit of ordering ‘a bit of beef between two slices of toasted bread’ when at the gaming table at London’s private clubs was an innovation in manners for the upper classes. Soon, this ‘new’ dish of salt beef in bread – which may have also been inspired by the Earl’s recent tour of the Ottoman Empire – was ‘highly in vogue’, observed French writer Pierre-Jean Grosley on a trip to London in the 1760s.

1850s – MUSTARD! MUSTARD!! MUSTARD!!!

By the mid-nineteenth century, according to historian Pen Vogler, sandwich bars had become hugely popular for London’s middle-class men. Joining the ‘hot and hungry’ crowds as they flooded out of performances at the Lyceum or Drury Lane after midnight, the flaneur George Augustus Sala – a contemporary of Charles Dickens – didn’t have need of the theatre. His entertainment was the cacophonous mass, ‘clamorous for sandwiches’ and piling into the shop on the corner of Bow Street to cries of ‘mustard’ and stacks of freshly cut ham, beef, and German sausage sandwiches. The scale of the sandwich fever was astonishing: according to journalist Henry Mayhew in 1851, in addition to the sandwich bars, there were also dozens of ham-sandwich street-sellers outside the theatres. This booming trade had been ‘unknown’ a decade earlier, and yet now there were over thirty of them, plus many more ‘anxious to deal in sandwiches’ who couldn’t muster the modest capital required.

1870s – THE UPPER-CLASS CUCUMBER COOLER

The upper-class afternoon tea – with little cakes, toasts, and sandwiches – was instituted gradually, from the end of the seventeenth century, according to historian Diane Purkiss. The fever for crustless and minute cucumber sandwiches, however, came on fast – ‘a sudden fashion’ of the 1870s, she goes on to note. These light and refreshing dainties were only available in summer, which meant the moment for them coincided perfectly with the social season for London’s high society. They arrived just in time for the first Wimbledon in 1877, were favoured by the officials of the Raj in India for their cooling properties, graced the tables of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887, and were most probably on the Ritz’s first menu when it opened in 1906.

1948 – THE BRITISH RAIL SANDWICH

Signs that the trend for sandwiches would begin to trough were evident soon after their mid-nineteenth century peak, though. For the snobbish London elites, predictably, it was when the dish travelled beyond the city that it started to lose its appeal. A sandwich on the move, procured at an unassuming railway station, was the lowest of all, utilitarian and stale. In 1869, Anthony Trollope derided the railway sandwich’s ‘whited sepulchre, fair enough outside, but so meagre, poor, and spiritless within’ as the ‘real disgrace of England.’ It certainly compared unfavourably to the French alternative, whose ‘nicely fitting slice of ham’ in a fresh, crusty loaf ‘made with the whitest and best flour’ and neatly tied with ribbon had been enough to set Dickens into a reverie three years earlier. Over the decades that followed, the British railway sandwich became something of a perverse national treasure – always so ripe for satire and denigration – and when the railways were nationalised in 1948, it graduated, too, to the ‘British Rail’ sandwich.

1959 – SALMON AND CHAMPAGNE

Reviving the glamour of the sandwich required a distinctively new setting. The visionary Lincoln’s Inn hostess Hilda Leyel had declared it so in 1925: the ‘proper accompaniment’ to a sandwich should not be the ‘railway station coffee, but a glass of champagne.’ But Leyel was ahead of her time, and a key ingredient of elegance was missing from her repertoire: smoked salmon. The cured fish was still something of a rarity in London in those days. It had arrived in the nineteenth century by way of East End smokehouses, which were set up by European Jewish migrants for making Scottish salmon. By the 1920s, it was on offer at the exclusive counters in Harrods Meat and Fish Hall, and found a home in Jewish delis like Panzer’s in St John’s Wood when it opened in 1944. But the sweet spot for the smoked salmon sandwich arrived in the late 1950s, with no one better to declare it so than Leyel’s great admirer Elizabeth David. Writing in Vogue in 1959, David imagined her perfect Christmas day at her Chelsea home ending with ‘a smoked salmon sandwich with a glass of champagne on a tray in bed.’

1960s – AS YOU LIKE IT

Londoners had already been clamouring for German sausage sandwiches slathered in mustard on the strand in the 1850s. So, when Paul Rothe migrated from Germany and set up one of London’s first Deutsche delicatessens in Marylebone in 1900, he had an eager crowd waiting for the ‘continental comestibles’ he sold. But according to its current proprietor, the shop didn’t start selling sandwiches until the 1960s, when the area became less residential and more business-oriented. The menu was – and remains – an extension of the delicatessen’s cornucopia: pretty much anything you can imagine, you can have in a sandwich. Though experimentation is encouraged, it’s worth starting the journey with the deli’s classics, like hot frankfurter with German mustard and sauerkraut, or egg mayo and four anchovies.

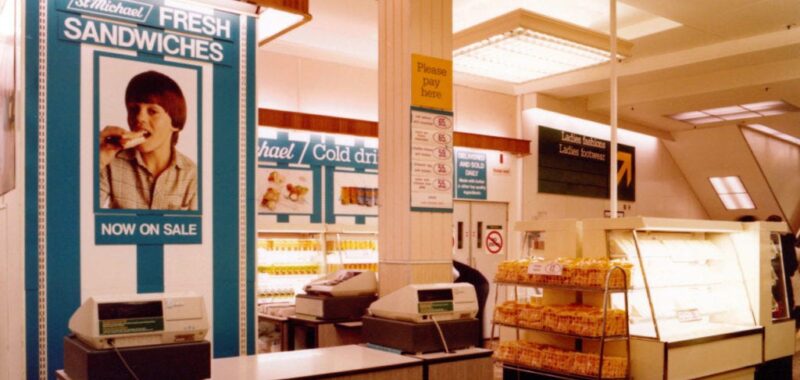

1980 – THE BOX-FRESH ONE

Central London’s 1980s were years of boisterous shoulder suits, big mobile phones, and boxed sandwiches. It all started in the Marble Arch Marks & Spencer store in 1980, when a shop assistant at the cafe decided to wrap up some unsold sandwiches and sell them to take away. Soon they were boxed up in plastic triangles and sold across several stores, with tomato and salmon being the first offering (the arrival of farmed salmon in the late 1960s had made it more affordable and available); a year later, the hugely popular prawn mayonnaise was introduced. By 1985, Boots had invented the Meal Deal, and the way the city’s workers lunched had changed irrevocably.

1980s – THE ALL-NIGHT BAGEL

In the same period, Londoners seeking the counterpoint to the functional fridge-cold triangle could take a late-night trip east for a bagel on Brick Lane, where smoked salmon, lox or herring bagels were the most popular items. At some point, a new bagel appeared: an unwieldy muppet mouth filled with teeth-tangling salt beef, gherkins prone to flying out like detached plane propellers, and mustard made for chin drizzles. Nothing about this dish was new: from the Earl’s beloved salt beef and the bagels boiled in Jewish bakeries since the 1800s, to the mustard so loved by the strand theatre crowds in the 1850s, London had seen this all before. But it was in the 1980s that Beigel Bake – which had opened in 1974 –began a twenty-four-hour operation and became an epicentre for this sandwich, serving crowds of revellers crying out for mustard after midnight like it was 1859.

1980s – THE GRILLED SLIPPER

Italians are notorious for their food conservatism: the old always trumps the new. But on the rare occasion that a novel food does find its way onto the Italian culinary map, they embrace it hard. Ciabatta (which means slipper in Italian) and panini sandwiches became popular in the 1980s due to simultaneous developments in Venice and Milan. Modern-day ciabatta was invented in 1982 by Arnaldo Cavallari, a miller from Veneto, as an Italian alternative to the baguette that he hoped would make him rich (spoiler: it worked). In Milan, meanwhile, the motorcycle-riding, Timberland-wearing paninaro youth subculture movement was gathering speed and embracing the panino as a meal that could keep pace with their lifestyles. By the end of the decade in London, the ciabatta panini was becoming increasingly widespread, available anywhere with a griddle, and helped by the rise of fast-sandwich spots like Costa Coffee and Pret a Manger (which opened their first shops in Westminster in 1981 and 1986 respectively).

1991 – THE EAGLE LANDS A STEAK ROLL

When The Eagle opened in Farringdon in the bracingly cold winter of 1991, it offered warmth in the form of space heaters and a steak sandwich. The pub’s first flyer listed the ‘Bifana’ at £4. The combination was simple – rump steak, salsa verde, cos lettuce, and a stone-baked Portuguese roll – but the effect was outsize. The sandwich became the rock steady of the pub’s otherwise changing menu. It’s been there every day since, as the pub has graduated legions of successful chefs – starting with Sam and Sam Clark, who met there before setting up Moro round the corner in 1997 – and moved from journalists’ canteen to culinary pilgrimage site.

1998 – NIGEL AND NIGELLA MAKE TRENDY FOCACCIA

In 1925, when Leyel envisaged the multitudinous possibilities of a good filling, she made just one exception: ‘Never put mushrooms into sandwiches; they are not safe to keep to eat cold.’ By the 1990s, though, the temperature on mushrooms had changed, and there was one in particular getting all the attention. The Portobello had hit London’s markets at the start of the decade, when mushroom farmers realised they could create a new product by letting button mushrooms grow a little longer. The nineties also saw two new trends in London sandwich-making: deli-style focaccia sandwiches, and a greater variety of vegetable-based options. There was no better pair to crystallise the currents of that decade than rising culinary stars Nigel Slater and Nigella Lawson. So, when they joined forces in the TV studio in 1998, Lawson chose the ‘fabulous’ oversized mushrooms for a vegetarian steak sandwich in ‘trendy focachee-ya’, as Slater called it. ‘It’s better than the usual vegetarian bap … one of those sort of wholemeal things with alfalfa in’, he mused. ‘It’s like tucking into a futon.’ The pair loved it so much, the recipe made it into both their cookbooks, Real Food (Slater) and How to Eat (Lawson), that same year.

2010s – BAKEHOUSE SOURDOUGH GOES BIG

If the fluffy focaccia and open-mouthed bagel seemed like reactions against the boxed fridge sandwich, for the eaters of the late 2000s they didn’t go far enough: London needed to go bigger, chewier, more manually impossible. Enter the sourdough bakehouse sandwich circa 2005. That’s the year Gail Mejia, who was already running The Bread Factory, a successful wholesale business, joined new partners to open the first Gail’s. Supposedly the team have been using the same sourdough mother for the bread they make their sandwiches with ever since, even as the company has now become a major chain. But the bakehouse boom truly set off in the 2010s, primarily out of east London: E5 Bakehouse opened in 2010, Dusty Knuckle in 2014, and Pophams in 2017. Drawing from a cosmopolitan, Mediterranean-leaning dictionary – from roasted roots to porchetta, dates to pomegranates, romesco to nduja, garlic yoghurt to wild garlic mayo – the new bakehouses all spoke the same language in unison, feeding it into vast wobbly wedges of walnut-brown, crater-surfaced bread.

2010 – THE NEW BACON SANDWICH

No one but no one thought it was possible to reinvent the bacon sandwich and make the new version a thing. The bacon sandwich is as everyday as it is delicious, and there are few ways to vary it without creating an altogether new dish (such as bacon, lettuce and tomato, or bacon, scallop and black pudding). But that changed in 2010, when Dishoom opened its doors. Here, finally, was evidence that a bacon butty isn’t always a bacon butty. Sometimes it’s a bacon naan roll, fresh from the tandoor, smeared with Philadelphia and served with coriander and tomato chilli jam.

2012 – SWEET DOUGH MAKES SWEET DOUGH

In the early 2010s, Londoners eating out at the city’s new burger restaurants – MEATLiquor (opened 2011), Honest Burgers (2011), and Patty&Bun (2012) – started to notice something unusual about the bread buns: they weren’t sesame-seeded crumbling pillows, but rich, doughy domes of brioche. By 2012, these slightly sweet buns were everywhere, even pubs. It was the mildly sickly trend that riled burger eaters from the start, and yet (perhaps reflecting a higher tolerance for sweetness in our palates in general) it has persisted.

2012 – THE PRIVATE MEMBERS’ CLUB ONE (2.0)

By the two-hundred-and-fiftieth anniversary of the Earl of Sandwich’s stroke of inspiration, it was high time someone came up with another legendary sandwich in a private members’ club. Chef Jeremy Lee obliged when he joined Quo Vadis as head chef in 2012 and brought a favourite sandwich with him: chunky smoked eel and fierce horseradish cream, neatly parcelled between two playing cards of golden grilled sourdough. Though not by design, there is an irony and symmetry to Lee’s move. Like the Earl before him, he’s taken a neglected working-class food, dressed it up anew, and turned it into a fashion irrevocably associated with his name.

2018 – THE HOT SANDO SUMMER

Whisper the word ‘sando’ any time before the summer of 2018 and you’d most likely have received a quizzical look. By July, though, TĀ TĀ Eatery’s Iberico pork sando was all anyone could talk about, with Bright soon following suit with its own panko pork and shredded cabbage version. Fast-forward to 2019 and TĀ TĀ Eatery had opened a specialist sando shop, TÓU (now at Borough Market); Soho izakaya Ichibuns had a celeriac version; Nanban was doing miso aubergine; there was sardine at Two Lights; Jidori was doing a cheeseburger one; and Peg was holding down the fort with pork. Nearly all of these restaurants have shut down since Covid, but another dozen spots across the city are now open, so customers can still get their fill.

2020s – THE DOORSTEP DINNER

The Covid lockdowns of 2020 and 2021 were supposed to hail the end of the sandwich: it only took the city’s workers vacating the centre for their homes to (temporarily) topple the regime of Pret’s chewy baguettes. But while one kind of sandwich lunch was on a downward spiral, another was on the rise. In place of utility, there were semolina subs filled with curls on curls of cold cuts – dizzying to look at, like an optical illusion (Dom’s Subs); fried and saucy things in focaccia thick enough to climb (Max’s Sandwich Shop); elaborate banh mi baguettes (Hai Café); and prized small-plates, usually featuring a fritter, squashed into bread (40 Maltby Street). Sandwiches became luxury, and doorsteps the new dining tables.

2024 – THE WHITE AND FLUFFY ONE

The early 2020s have seen London’s sandwiches growing in complexity and size, but there are also countervailing winds. In sandwich-land, it’s time for cloudy simplicity and sweet childhood fillings, taking inspiration from the cafe and bakery cultures of East and Southeast Asia. There are fluffy and pale egg sandwiches to be had with milk tea at Hong Kong-style cafes, Singaporean kaya toast with creamy coconut jam (kaya) and salty pats of butter, and stacks of perfectly oblong shokupan (Japanese milk bread) at bakeries like Happy Sky (though temporarily closed) and Arôme.

2024 and Beyond – SANDWICH…SANDWICH?

We can only wonder blindly about the next great London sandwich moment…

How thick the cut? And how stacked the filling?

Will the primacy of the visual cross-section finally trump flavour and coherence all together?

How tautological will the brand name be?

Where will the far flung culinary influences be plucked from this time?

If trends in London wraps and the terrifying advent of the Yorkshire Burrito are anything to go by, perhaps it’s time for a little more regional influence. Perhaps the New Ultimate Sandwich in London will come from somewhere like…Bristol? Perhaps it will be called…Sandwich Sandwich.

Hester van Hensbergen is a writer with a focus on food and the environment. She writes for Vittles, the Times Literary Supplement, Eater, TANK Magazine and others. She is Programme Manager for the Oxford Real Farming Conference, the annual gathering of the UK’s agroecological food and farming movement. To see what she’s been writing and cooking, find her on Instagram @hestervanhensbergen.

This piece was edited by Adam Coghlan and Jonathan Nunn, and sub-edited by Sophie Whitehead.

For further reading on the history of the sandwich in Britain, see the relevant chapters in Pen Vogler’s Scoff: A History of Food and Class in Britain (2020) and Diane Purkiss’s English Food: A People’s History (2022).