This is part of Slate’s 2024 Olympics coverage. Read more here. If you’re enjoying our coverage from Paris, join Slate Plus to support our work.

The Games won me over.

I had written critically about the Rio Games, the Tokyo Games, and public money for sports stadiums more generally. I’m still suspicious of the IOC, bored by the pretentious Olympic mythology, and very doubtful that the competition does good for its host cities.

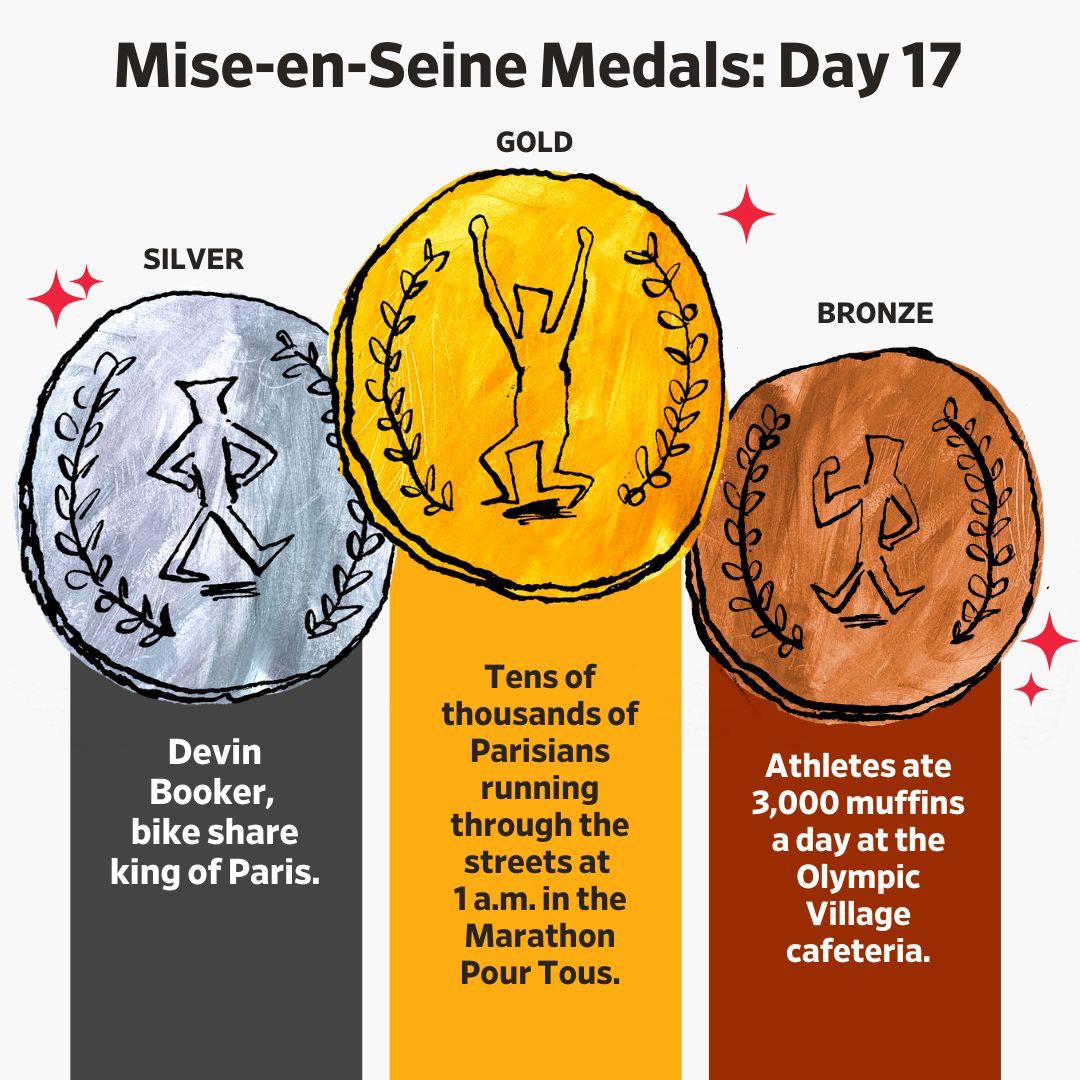

But the bias of the Olympic press coverage in Paris is that simply by being here, you become a participant in the thing you’re trying to evaluate. Or at least I did. I felt the Algerians shake Chatrier with their chants of “Imane, Imane.” I marveled at the dinky ping-pong serves and the monster volleyball blocks. I offered my high-five to the sweaty-handed joggers in Saturday night’s “marathon for everyone,” which gave tens of thousands of regular people a race down the official course at 1 in the morning. I even loved the golf, which surprised me by being the Olympics’ most egalitarian spectator experience, all ticket holders equal in our dignified scrambling up the grassy hillocks around the course.

Even beyond the interviews I sought out and the events I bought tickets for, the Olympics were all around me—blocking my way to the subway, sure, but also sneaking up on me in surprise encounters. Team doctors in the Métro, a track star getting a massage on the side of the road, those inescapable volunteers with their coveted pink hats. There were so few cars some days I got used to walking in the middle of the street.

“Paris Superstar,” read the cover of Saturday’s Libération, the left-wing daily that can usually be counted on for Olympic cynicism. To understand the hype, it helps to recall that all of France was dreading this. Even the mayor of Paris was saying the public transportation system wasn’t ready; the government published a plea for remote work, debunking “prejudices” about télétravail. “Remote work doesn’t necessarily mean staying in your house!”

The transition from Olympic dread to bliss is not new; Londoners underwent a similar epiphany in 2012. But the French weren’t just dreading the Games; they were doubting that Paris could even pull it off.

And so the goalposts for Olympic success shifted in a way that was favorable to the organizers. To use a more precise Olympic metaphor, Paris set the bar so high people forgot why they were trying to jump over it in the first place. The question became: Can Paris pull this off?

The answer to that has been a resounding ouais. The key infrastructure was completed in time. The masked torchbearer of the opening ceremony did not fall to their death from the slippery wet roof of the Musée d’Orsay. The Seine miraculously tested negative for bacteria on race days. The no-build model didn’t just work; it was beautiful. The Games were embedded in the city on television and in person. The scattering of venues across the metro area allowed distinctive local traditions to emerge around each sport’s culture, like the impromptu ping-pong HQ in a Chinese restaurant in the 15th arrondissement. That decentralization was possible in turn because the city’s policy to discourage driving and encourage walking, biking, and public transit proved more than up to the task of moving hundreds of thousands of spectators around each day.

But the Olympics weren’t some end-of-term exam that Paris had to pass. Policymakers decided a decade ago that having the Olympics in Paris wasn’t just possible but a great idea.

Those are the terms on which these Games should be evaluated. It may take years before we know the full impact—before we find out if the kids in Seine-Saint-Denis learned to swim, before we watch the Olympic Village become a neighborhood, before we see if this “magic interlude,” as the press here insists on calling it, puts French politics on a new path.

The Olympics probably did help the Paris region do the things it wanted to do, faster, including build a new train station, complete thousands of units of new housing, clean that river, and improve bicycle infrastructure. One journalist told me about a conversation with the planner of Germany’s 2006 World Cup, who said that it was like getting the house ready for a marriage: You take care of all the things you’ve been meaning to do. I believe officials when they say, as they have said over and over and over again, that this and that would not have happened if not for the Olympics.

But who was all this money and effort for? Ticket buyers were just 62 percent French, and fewer of those were Parisians. The supposed benefits of the Olympics for the local economy are going to be a huge disappointment. Already we know that the capital’s museums have seen massive attendance declines; now there is talk of a state fund for financial assistance to cultural institutions—as if Paris were recovering from a hurricane, rather than concluding a giant two-week festival. It’s hard to imagine what kind of “image boost” could possibly accrue to this most overexposed of cities or to see how a 76 percent rise in the capital’s number of Airbnbs is a positive development.

So, Paris reinvented the Olympics, but to what end? Other cities may pursue the idea of a no-build, car-free Games, but other cities are not Paris, with its superb public transit, wonderful public spaces, and street life that made the Olympics a legitimate citywide happening. But it was fun while it lasted.