No one has ever seen axions. But scientists have theorized their existence as a way to explain some of the biggest questions in particle physics, including the nature of dark matter, the mysterious substance that constitutes most the mass of the cosmos. Confirming the existence of axions could lead to insights into the history and composition of the universe itself.

Now, in a groundbreaking experiment, a team of scientists led by Harvard and King’s College London have made a significant step toward using quasiparticles to hunt for axions, which are hypothesized to actually make up dark matter. The findings, recently published in Nature, open new realms for harnessing quasiparticles to search for dark matter and develop new quantum technologies.

“Axion quasiparticles are simulations of axion particles, which can be further used as a detector of actual particles,” said senior co-author Suyang Xu, assistant professor of chemistry. “If a dark matter axion hits our material, it excites the quasiparticle, and, by detecting this reaction, we can confirm the presence of the dark matter axion.”

Frank Wilczek, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who first proposed axions, credits these findings as a major breakthrough in the study of these particles.

“The jury is still out on the existence of axions as fundamental particles that beautify the basic equations of physics and provide the cosmological dark matter,” Wilczek said. “But now, thanks to these ingenious new experiments, we know for sure that the Nature makes use of the underlying ideas. Axions now join holes, phonons, plasmons, and a handful of other ‘quasiparticles’ we find emerging as ingredients of matter, available for new scientific and technological creations.”

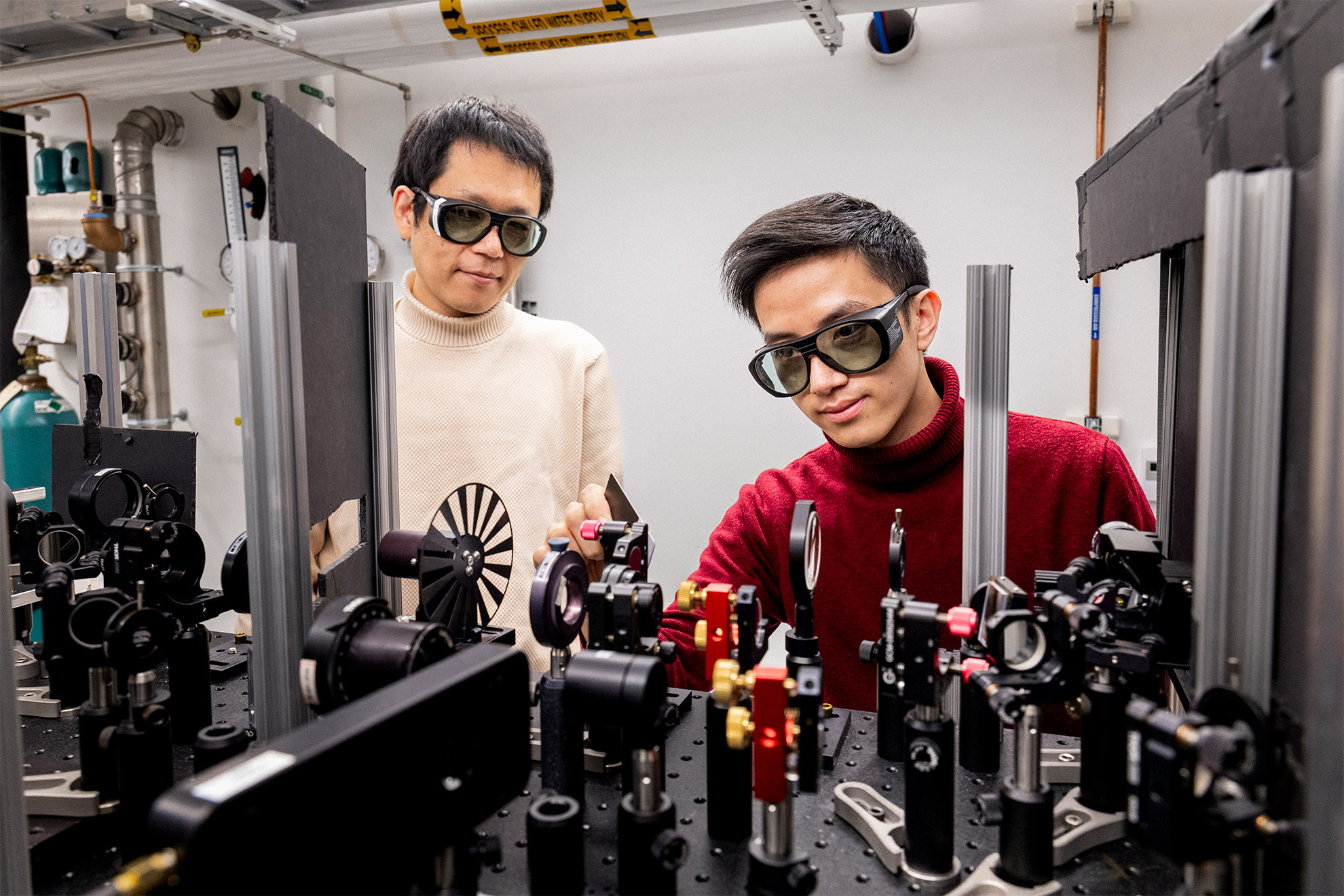

The experimental work was led by Jian-Xiang Qiu, a Harvard Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences student in the Xu lab. Researchers who assisted in the study include Yu-Fei Liu, Anyuan Gao, Christian Tzschaschel, Houchen Li, Damien Berube, Thao Dinh, Tianye Huang, as well as an international team of researchers from King’s College, UC Berkeley, Northeastern University, and several other institutions.

The researchers utilized manganese bismuth telluride, a material renowned for its unique electronic and magnetic properties. By crafting this material into a 2D crystal structure, they established a platform ideal for nurturing axion quasiparticles. This process involved precision nano-fabrication engineering, in which the material was meticulously layered to enhance its quantum characteristics.

“Our lab has been working on this kind of interesting material for almost five to six years, and it is both a very rich material platform and also it is very difficult to work with,” said first author Qiu. “Because it’s air-sensitive, we needed to exfoliate down to a few atomic layers to be able to tune its property properly.”

Operating in a highly controlled environment, the team coaxed the axion quasiparticles into revealing their dynamic nature in manganese bismuth telluride. To accomplish this delicate feat, the team utilized a series of sophisticated techniques including ultrafast laser optics. Innovative measurement tools allowed them to capture movements of axion quasiparticles with precision, turning an abstract theory into a clearly visible phenomenon.

By demonstrating the coherent behavior and intricate dynamics of axion quasiparticles, the researchers not only affirmed long-held theoretical ideas in the field of condensed-matter physics but also laid the groundwork for future technological developments. For example, the axion polariton is a new form of light-matter interaction that could lead to novel optical applications.

In the field of particle physics and cosmology, this new observation of the axion quasiparticle can be used as a dark-matter detector, which the researchers have described as a “cosmic car radio” that could become the most accurate dark-matter detector yet.

Dark matter remains one of the most profound mysteries in physics, constituting about 85 percent of the universe’s mass without detection. By tuning into specific radio frequencies emitted by axion particles, the team aims to capture dark-matter signals that have eluded previous technology. The researchers believe it could help discover dark matter in 15 years.

“This is a really exciting time to be a dark-matter researcher. There are as many papers being published now about axions as there were about the Higgs-Boson a year before it was found,” said senior co-author David Marsh, a lecturer at King’s College London. “Experiments proposed that axions emitted a frequency in 1983, and we now know we can tune in to it — we’re closing in on the axion and fast.”

Xu is confident that the team’s multifaceted approach enabled their pioneering success.

“Our work is made possible by a highly interdisciplinary approach involving condensed-matter physics, material chemistry, as well as high-energy physics,” Xu said. “It showcased the potential of quantum materials in the realm of particle physics and cosmology.”

Moving forward, the researchers plan to deepen their exploration of axion quasiparticles’ properties, while refining experimental conditions for greater precision.

“The goal for the future is obviously to have an experiment that probes axion dark matter, which would definitely be super beneficial for the whole-particle physics community that is interested in axions,” said senior co-author Jan Schütte Engel, a physicist at UC Berkeley.

This research was partially funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, and the National Science Foundation.

Source link