Scholars at Harvard tell their stories in the Experience series.

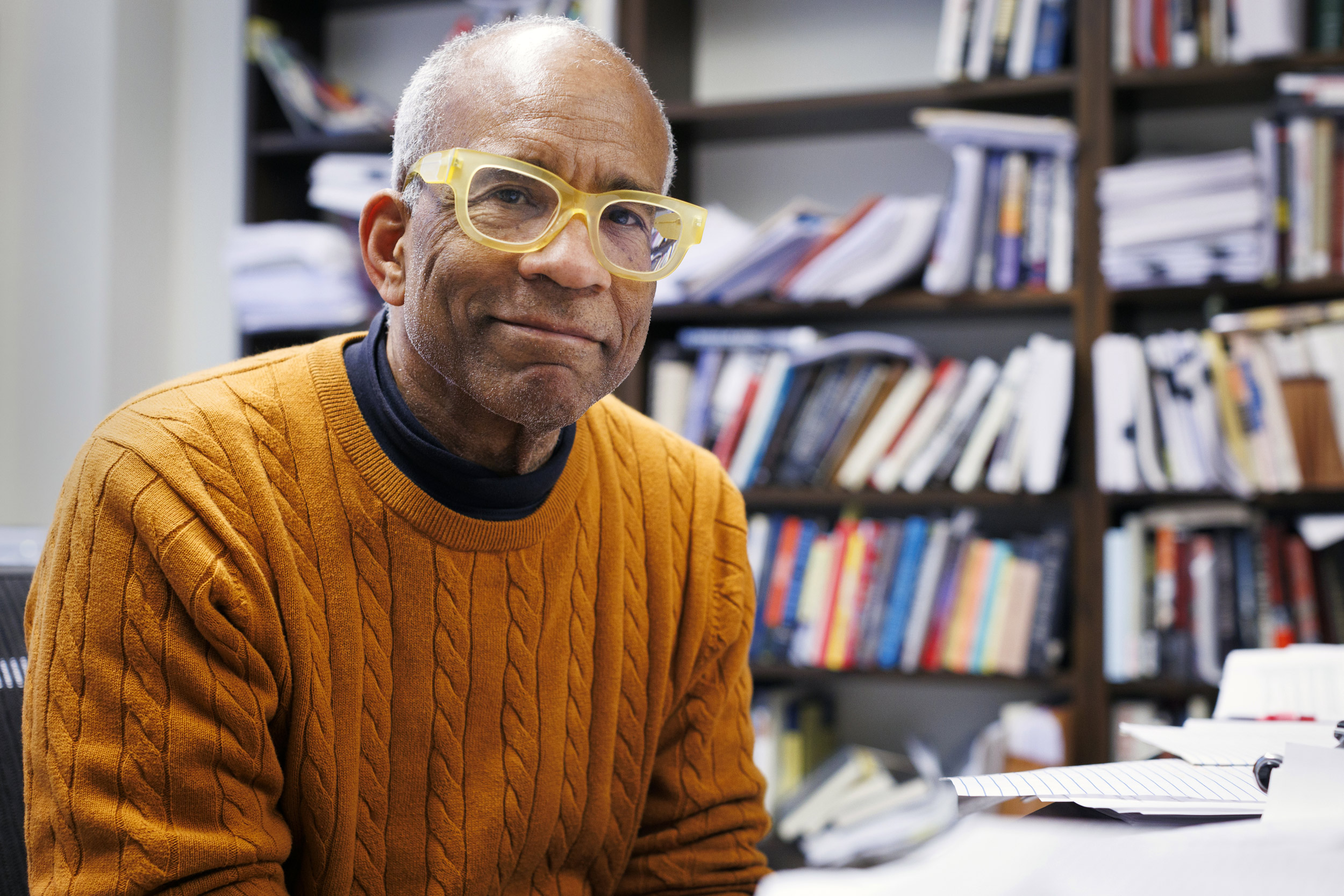

Lawyer and legal scholar Randall Kennedy can fairly be described as something of an iconoclast.

As a public intellectual, he is known for his openness to different points of view and his nuanced and sometimes provocative opinions about issues such as affirmative action (there are costs along with benefits), racial profiling (not completely nonsensical but ultimately discriminatory), Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion statements (abandon them), and some other issues typically associated with the left.

Kennedy, the Michael R. Klein Professor of Law, has also been unafraid to engage with the right. In 2020, the conservative Manhattan Institute invited Kennedy, a longtime questioner of critical race theory, to participate in a discussion on the topic. He eventually took other CRT critics on the panel to task for being too categorically dismissive.

“The great thing about his work is that you can never predict where he will end up — on racial justice, he sometimes seems conservative, sometimes liberal,” said then-Law School Dean Martha Minow in a 2013 profile of Kennedy. “In his field of race and the law, he is unique in the legal academy. I don’t know anyone else who has his commitment to pursuing the truth about controversial issues to wherever it goes.”

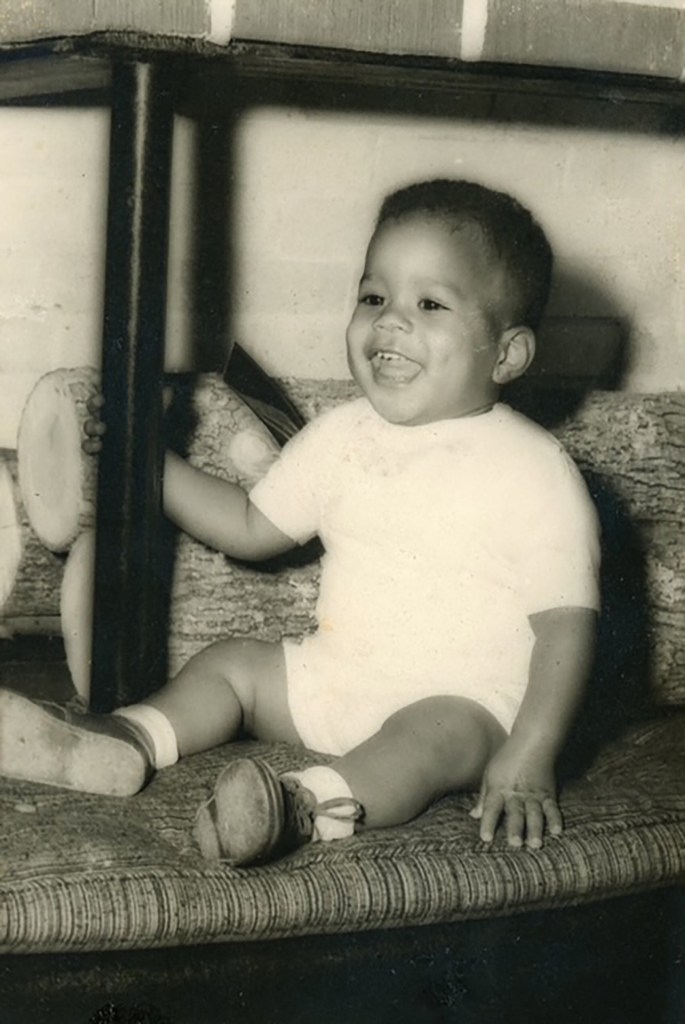

Kennedy, 70, was born in Columbia, South Carolina, and raised in Washington, D.C. His family’s move north from the Jim Crow South, along with his father’s pessimism about prospects for lasting racial justice in the U.S., left a deep imprint on Kennedy’s intellectual life.

The son of a postal worker and a schoolteacher, Kennedy attended the prestigious St. Albans School, did his undergraduate studies at Princeton, and was a Rhodes Scholar. He attended Yale Law School and has taught at Harvard since 1984. The author of seven books, Kennedy recently spoke with the Gazette about his life, career, and views on racial equality in the U.S. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Why did your father decide to move the family from Columbia to D.C.?

My parents were refugees from the Jim Crow South. My father was from Louisiana. My mother was from South Carolina. My father was a postal clerk and my mother a schoolteacher. They met at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, during World War II.

In the mid-’50s, soon after my birth, they left. An incident precipitated their move. It involved my father. He carried a gun as part of his employment driving a truck with the postal service. In some little town in South Carolina a white policeman stopped him. The policeman said, “We don’t allow negroes to have guns. Surrender yours.”

My father refused, and they had a standoff. My father got out of there fast, made it to Washington, D.C., got on the telephone, and said to my mother, “We’re moving.” Years later, I asked my father why he had left inasmuch as he and my mother had just built a house outside of Columbia. He said to me the following: “I thought that if we did not move, I was going to kill a white man, or a white man was going to kill me.”

Did you experience discrimination while you were growing up?

Yes. The most memorable episodes transpired during trips from D.C. to South Carolina for holidays. Even as a kid, I sensed how the atmosphere changed as soon as we went over the 14th Street Bridge from D.C. into Virginia.

I remember a couple of times when my father was stopped by the police as we were driving in Jim Crow territory. The scenario was the same. A policeman would pull our car over. My father would ask, “Is there a problem, officer?” and the officer would say, “No, there’s no problem. I pulled you over because I noticed you have Washington, D.C., license plates, and I wanted you to know that we do things differently down here.”

The policeman was testing my father, and my father played along. He did what the police officer wanted, and what the cop wanted was for my father to call him “sir,” and be deferential, show that my father knew to stay in his place.

My father performed as required, and we went on our way. God bless my father for that! He put as his highest priority the well-being of his family. If he had to swallow his pride to accomplish that aim, so be it. What commitment. What poise. What discipline. What love. Yes, God bless my father for that.

How did your parents’ views on race influence you?

They influenced me greatly in all sorts of ways, some of which undoubtedly are beyond my conscious awareness. One was my father’s bone-deep pessimism about the possibility for lasting racial justice in America. He believed that the United States of America was created to be a white man’s country and would always be a white man’s country, and he never forgave the United States for its mistreatment of African Americans.

At his burial, because he was a veteran, a representative of the U.S. military was on hand to deliver an American flag, nicely folded, to my mother. I remember looking at my brother and smiling amidst the tears. We both knew that our father would have found this scene uproariously funny because my dad was not a patriot. He was an anti-patriot. The effort to understand the sense of aggrievement that he felt has been a big part of my intellectual life.

What memories do you have of your childhood?

I had a wonderful childhood! I spent several summers in Columbia, South Carolina, where I would stay with my Aunt Lillian. I had a great time even though during some of those summers no public parks were open. Why? Because South Carolina preferred to close the public parks rather than see them desegregated. But I had lots of friends, and we had lots of fun.

I also recall my childhood in D.C. with fondness. My parents bought a house two blocks from the Takoma public park. It was at that park that I learned to play football, baseball, and, most importantly, tennis. The tennis courts at Takoma public park are named after my father, Henry Kennedy Sr. He was known as “Mr. Tennis.”

To support his tennis-playing children, he learned everything that he could about the game and became quite proficient as a teacher and organizer of tennis tournaments. When he passed away, people in the neighborhood successfully petitioned the city government to name the tennis courts in his honor.

Is it true that you were a very good tennis player in your teens and that you played against Robert McNamara, who was then secretary of defense under President Lyndon Johnson?

I was a very good junior tournament player, as was my brother. He and I took care of the tennis courts at the St. Albans Tennis Club in Washington, D.C., on the grounds of the National Cathedral.

On Sunday mornings we were supposed to close the courts down during the Cathedral service. Usually, we did. But occasionally Defense Department Secretary Robert McNamara and National Security Adviser Walt Rostow would show up and beseech us to allow them to play. We even played doubles with them from time to time.

On one occasion, a chauffeur came to the courts and announced that the president was on the phone and wanted to speak with McNamara right away. The secretary left for a few minutes, returned, and play continued.

McNamara and Rostow were both quite competitive, but Rostow was the better of the two.

I read that tennis allowed you to attend the prestigious St. Albans School.

When my brother began taking care of the tennis courts at St. Albans, I would help him. When courts were open, and few people were around, I would practice with him.

The head pro at the club, who was also the tennis coach at the St. Albans School, saw me play and contacted my parents about applying to the school. They told him right off that we didn’t have St. Albans-level money. He told them that he could get me a scholarship if I could gain admission.

I ended up applying, gaining admission, and playing No. 1 on the school varsity from the eighth grade to the 12th.

I’ve gone to very fine schools, but the most transformative was St. Albans, where I fell under the sway of my favorite teacher, John F. McCune, known to generation of boys as Gentleman Jack McCune. He was my American history teacher and introduced me to the work of Richard Hofstadter at Columbia University and C. Vann Woodward at Yale University.

Reading their books changed my life. It was Mr. McCune who got me interested in the politics of historiography. He was a thoroughly inspirational figure. We shared a birthday and became close friends. I was with him the day before he died and was honored to speak at his memorial service at the National Cathedral.

“Anybody who labels me conservative has not paid attention to what I have written over the course of my life.”

How did you become interested in law?

Lawyering as an idea was an active presence in my household. My father spoke often about the time that he saw Thurgood Marshall argue the South Carolina whites-only primary case, Rice v. Elmore, in 1947.

The plaintiff was a Black business owner by the name of George A. Elmore, who challenged the exclusion of Black voters from the South Carolina Democratic primary. The judge ruled that the Democratic Party of South Carolina could no longer exclude qualified negroes from participating in primary elections.

And my parents were very proud of their friendship with the leading Civil Rights attorney in South Carolina, Matthew J. Perry. Most influential, however, was the example set by my brother, a 1973 graduate of HLS, who became a prosecutor, a Washington, D.C., judge, and then a judge on the United States District Court in the District of Columbia. (When he retired, he was replaced by Ketanji Brown Jackson, who now sits on the Supreme Court.)

You seem to have great admiration for your brother Henry.

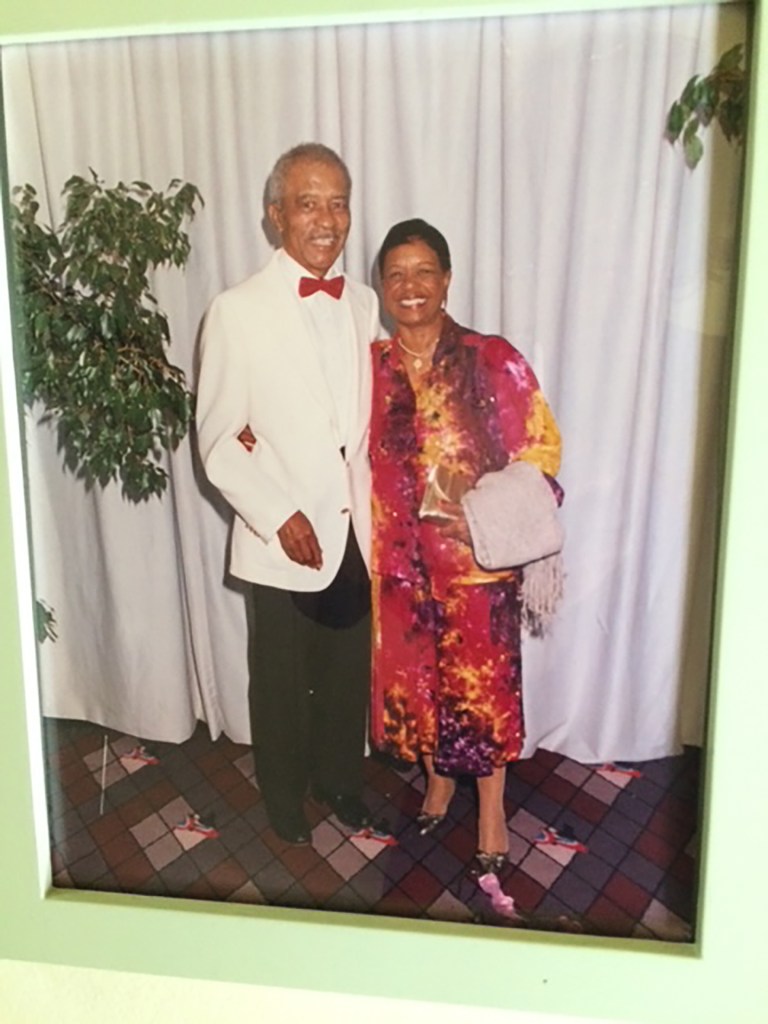

Yes. He was a conscientious jurist and is a remarkably encouraging and loving big brother. He has been a wonderful cheerleader for me and our younger sister, Angela, who is also an attorney. He has been especially important to me since my wife passed away.

Could you tell me how you met your wife?

My romance with Yvedt L. Matory began when I was a first-year student at Yale Law School, and she was a second-year student at Yale Medical School. We had met previously when she attended Sidwell Friends School, which was a 15-minute walk from St. Albans.

We married in June 1985 and had three children. She was a surgical oncologist at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She died of melanoma when she was only 48 years old. She passed away two months shy of what would have been our 20th wedding anniversary. I have lived a charmed life. The great tragedy that befell it was the death of my wife of blessed memory.

You served as a clerk to Justice Thurgood Marshall in 1983-1984. Can you talk about that experience?

It was thrilling to be able to work with and for “Mr. Civil Rights.” (Two of my co-clerks, by the way, are esteemed colleagues here: Terry Fisher and Howell Jackson.)

A strong argument can be made that Marshall was the greatest lawyer in American history. Think about the variety of posts he held — counsel for the NAACP, court of appeals judge, solicitor general, and Supreme Court justice — and the difficulties he had to overcome to make such positive contributions to American life and law!

I learned a lot working in the Marshall chambers. Seeing him up close was an inspiration that has deepened over time as I’ve gained a better sense of what he was up against and the patience, tenacity, poise, and grit that he displayed over a long period of time.

Did your father get a chance to meet Marshall?

My father met Justice Marshall on the next to last day of my clerkship. My father told “Mr. Civil Rights” how inspiring it had been to see him in that courthouse fighting for Black folks’ rights in a fashion that elicited grudging respect even from racist enemies.

How did you come to Harvard Law School?

When I left Yale Law School, I was all set to go work for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund after my clerkships with Judge J. Skelly Wright and Justice Marshall.

But near the end of my third year of law school, I got a telephone call from HLS Dean James Vorenberg, who invited me to the Law School to talk with him and other members of the faculty about a career in legal academia. I shall always be grateful for his solicitude.

When I talk about my fondness for HLS, some friends tease me, calling me a Pollyanna. Too bad! It’s hard for me to imagine a better setting for a professor than Harvard Law School. I have been surrounded for nearly 40 years by wonderful colleagues and students. Working here has been a blessing.

What role does teaching play in your career compared to research and writing?

I thoroughly enjoy research and teaching and am engaged in writing all the time. The course that I’ve taught the most is contracts. For a long time, I felt considerable anxiety before every class. Over the past decade, though, that anxiety has steadily dissipated. Now teaching contracts is wholly fun. One of my upcoming books will be about contracts in the context of intimate associations — friendship, dating, marriage, surrogacy, adoption, etc.

Much of my teaching and almost all of my writing thus far has been about the regulation of race relations. I am about to complete a book on which I have been working for nearly a decade. It responds to the following question: How did protests over racial injustice in the mid-20th century change American law? I seek to answer that question in 800-plus pages.

“I am deeply alarmed by the effective mobilization of racial resentment that has gripped American politics.”

You wrote a book that examines the historical, cultural, and social significance of one of the most offensive words in the English language. Can you talk about it?

It is my only best-seller and has generated considerable controversy. It provoked an attempted assault at a bookstore reading and has triggered walkouts. It has also prompted lawyers to seek my assistance as an expert witness in employment discrimination suits, union grievance actions, and prosecutions for murders and assaults in which I have testified for the defense in some cases and for the state in others. By the way, the full title of my book is “Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word.”

There were many people who said, “Well, you could have titled your book something else,” and there were people who would say, “You’re just trying to be sensationalistic.” My main goal was to educate, but how do you educate? If you’re boring, you’re not going to educate. You have to do something to get people’s attention and keep people’s attention. Do I try to do that? Sure, I try to do that. But I don’t view it as a bad thing.

Some in the media have, at times, labeled you a conservative. How do you respond to that?

Anybody who labels me conservative has not paid attention to what I have written over the course of my life. I believe that the United States is afflicted by unjustifiable hierarchies and inequalities that generate avoidable social misery. I think that it is scandalous that in a country this wealthy, there are so many people who are insecure regarding nutrition, shelter, healthcare, employment, and personal security due to crime and poor policing. I am in favor of reforms that aggressively address these problems.

The intellectual and ideological communities I find most attractive find voice in magazines such as The American Prospect, Dissent, The Nation, and The London Review of Books. If that makes me conservative, so be it.

I think that some observers have erroneously pegged me as conservative because I savor the company of intelligent conservatives such as my recently departed friend and colleague Charles Fried, because I participate enthusiastically in programming sponsored by conservative organizations such as the Federalist Society, because I strongly criticize certain policies such as mandatory Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion statements for university hiring and promotion, and because I indulge in certain rhetorical gestures that raise eyebrows — such as my use of the word “negro,” a term that I began using in 1984 at the insistence of my boss Thurgood Marshall and continue to use in homage to him and A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evers, W.E.B. Du Bois, my grandmother Lillian Spann, “Big Momma,” and countless other admirable souls.

You said that your father was pessimistic about the possibility of achieving lasting racial justice in America. What is your view?

Yes, my father was a pessimist on the race question. He did not believe that we shall overcome. The tradition he voiced is a strong tradition that includes the likes of Thomas Jefferson, Alexis de Tocqueville, Abraham Lincoln, Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and Derrick Bell. Tragically, there is much to which proponents of this tradition can point to substantiate their view that racial justice in America is doomed.

I place myself, however, in a different tradition, the tradition expounded by Frederick Douglass and Martin Luther King Jr., the tradition that embraces the possibility, indeed the likelihood, that racial decency will become an increasingly large and influential feature of American life.

I am deeply alarmed by the effective mobilization of racial resentment that has gripped American politics. But I take solace ironically in recognizing that a substantial part of that menacing reaction stems from remarkable successes in racial reform.

When I was born on Sept. 10, 1954, my home state of South Carolina explicitly subjected African Americans to a degraded, stigmatized status. It was not alone. Pigmentocracy was pervasive.

Yet, within a lifetime, by dint of remarkable struggles undertaken by Americans of all complexions, things changed sufficiently to enable a Black man to be president of the United States — a Harvard Law School alumnus who comported himself with consummate intelligence, grace, and honor.

Finally, what advice do you have for young lawyers?

Keep the fun quotient high by finding work that you love.

Source link