Growing up near the historic mud-brick city of Agadez, Nigerâs gateway to the Sahara, Mariam Issoufou was always inspired by the majestic adobe structures around her. The 27-metre-high minaret of the cityâs mosque, the tallest mud-brick structure in the world, has stood on the sandy horizon since the 16th century. But Issoufou never imagined that becoming an architect, and building such things herself, was a possibility.

âThere were no role models,â she says. âI didnât know of any architects in Niger, let alone any women in the field.â

When she had the chance to study in the US in the 1990s, it was the dawn of the tech era, and computers seemed like the most promising route to a stable career. âSo I became a software engineer. I worked in the industry for almost 10 years, and didnât like a minute of it.â

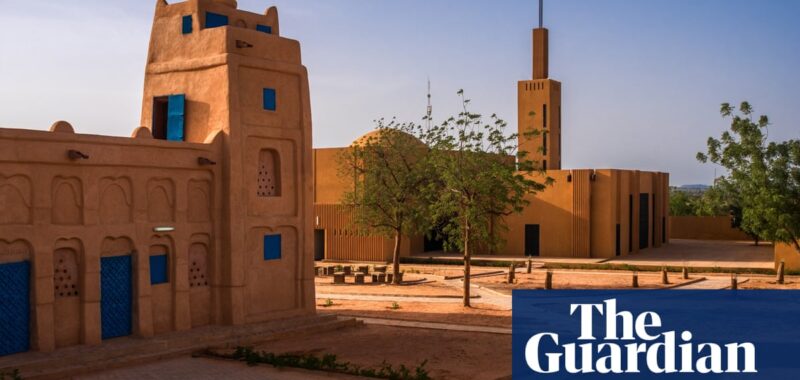

Just over a decade since Issoufou left the tech world and went back to university to retrain, she has established herself as one of Africaâs most sought-after architects. She has built a prize-winning library and mosque complex in the Nigerien village of Dandaji, as well as a celebrated earth-walled housing complex in the capital, Niamey, shortlisted for the Aga Khan award.

She is now working on a museum in Senegal and a presidential centre in Liberia, along with projects in Sharjah and Brazil. This is on top of her role as a professor at ETH Zürich, juggling offices between there, Niger and the US.

âBecause I came to architecture as a second career, I was more mature and incredibly single-minded about where to direct my energies,â says the 45-year-old, speaking from her new studio in New York City. âI knew exactly what types of problems I was interested in.â

Issoufouâs work is defined less by a single style and more by hard-nosed pragmatism, driven by a desire to get the best out of what is already locally available, be it materials or skills. Growing up in Niger, one of the poorest and hottest countries in the world â where 45% of people live below the poverty line and temperatures can exceed 45C â she was always baffled by the desire to emulate the west.

âOur built environment is shaped by the idea that progress must look like the western world,â she says. âThatâs the only image of progress that we have, and unless youâre able to achieve that, youâre somehow lacking. I found that incredibly insulting, and it didnât make sense.â

Issoufou had experienced first-hand how well the mud-brick buildings functioned in the desert climate, shielding interiors from the searing sun and releasing the heat back out at night, when temperatures plummet. She realised that earth was the most cost-effective and sustainable solution, in terms of construction, maintenance, energy consumption and local availability. Yet it has been an uphill struggle to convince her clients.

âI have to reassure them that Iâm not trying to send them back in time 200 years,â she says. âIronically, I have to show them examples of earth architecture in Europe for reassurance. We still defer to European standards as the authority, which is profoundly unfortunate.â

The housing project in Niamey, designed with the collective united4design, has provided a powerful proof of concept. The six courtyard homes, built on a plot that would usually house a single family compound, are a model for how the city could densify to avoid relentless sprawl. Built with unfired earth bricks and designed around passive ventilation principles, they are 10 degrees cooler indoors than out â whereas an equivalent concrete building would require air conditioning to be remotely habitable.

âSome months, as much as half of a personâs pay could go to the electricity bill because of AC,â says Issoufou. âThe use of earth isnât just better for the environment but for sustaining the economic life of the building, the people using it and those involved in constructing it. Sustainability has to be seen as this multilayered, intersectional thing.â

In Issoufouâs eyes, the term has become abused, driven by a self-serving industry that mandates expensive, box-ticking add-ons, which are energy-intensive to produce and not actually sustainable for most of the world.

She takes the reverse approach to how most of the global architecture industry usually operates. âI donât do a design then find who could build it,â she says. âI try to figure out who is there and what they know how to do. And then I design, keeping that in mind.â

Each project begins with a deep period of research, âexcavating the past of the place and understanding the practices that are currently thrivingâ, before the design process can even begin.

In the Liberian capital, Monrovia, Issoufou is designing the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development, named after the countryâs first woman president. The complex takes the form of a cluster of tall, steeply pitched blocks, inspired by traditional palava huts, whose exaggerated roofs were designed to manage Liberiaâs heavy rainfall.

after newsletter promotion

Inside, the steep timber roofs will be lined with mats of woven palm leaves made by local women, after Issoufou saw them weaving baskets on roadsides all over the city. âRather than importing materials,â she says, âwe are using raw earth bricks, fired clay bricks, rubberwood and palm leaves â all things that local builders and craftspeople know how to do, helping to promote economic sustainability.â

In the Senegal region of Kaolack, Issoufou was initially hesitant about taking on a project for the new Bët-bi museum, commissioned by Le Korsa, part of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. Museums had always made her feel uncomfortable. âWe accept this idea that museums are temples of culture that will somehow elevate you as a human, and you will learn a whole bunch of things there,â she says. âBut itâs very much a learned behaviour, from a certain place in the world.

âMuseums came to be because of colonisation and the expansion of empire, and the need to showcase all these plundered objects. In Africa, everyone complains that museums are built and then sit empty, and no one visits. But it makes sense that we, as a colonised people, would have no interest in them.â

She realised that the most successful parts of cultural buildings on the continent are always the public spaces outside. âIâve seen examples in Niger of massive museums that no one goes inside, but the landscape outside is full of people picnicking under the trees and spending a fantastic time together.â

In response, Issoufou decided to bury the Senegal museum, making it secondary to a series of inviting public spaces which gradually lead people towards the galleries, through glimpses of what lies below ground.

The triangular form was inspired by the Indigenous Serer people, who hold a deeply mystical relationship with the natural elements. The sun, wind, water and ancestral spirits are defined by a series of triangles between the living and the dead â while sinking the collections below ground was also a nod to ancestral burial practices.

âIâm trying to avoid the wilful grandness of a museum, which I feel can be incredibly intimidating,â says Issoufou. âHere, people will hopefully be seduced inside by seeing the content through apertures as theyâre going down the ramp. But you donât have the pressure of going inside if you donât want to.â

Back in Niger, a project for an earth-brick office building was nearing completion last year when the country was upended by a military coup in July. The building is slowly getting back on track, but Issoufouâs project for a cultural centre in Niamey, in a series of elliptical earth-brick towers, now looks unlikely to be realised.

âThe city worked really hard to find the funding, and we were two months away from breaking ground,â she says. âBut we have much bigger problems at this point.â

Still, she remains optimistic about the future of both the country and the continent. âIt feels as if weâre going through a second independence,â she says. âWe are seeing every arena in Africa, from fashion to banking, really involved in finding solutions that reflect our realities and our identities.

âThereâs a lot to be built still: we have this amazing canvas, waiting to be painted.â