Image source, Getty Images

- Author, Mark Savage

- Role, Music Correspondent

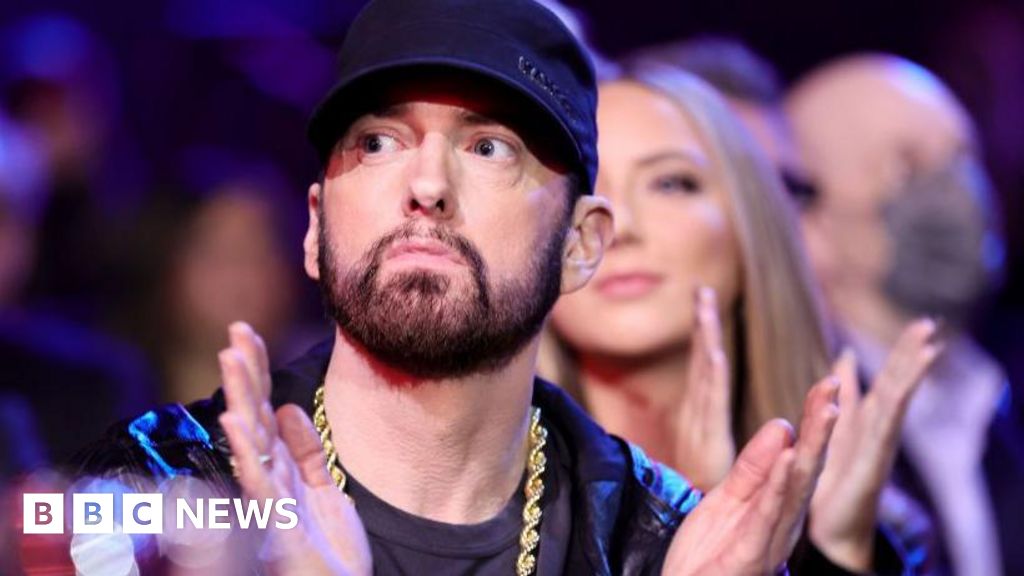

Spotify has won a long-running court case, in which it was accused of streaming Eminem’s music without permission.

They sued the music company for approximately £30m, saying that the star had never received full payment for songs like Lose Yourself and Without Me, which have been “streamed on Spotify billions of times”.

But a judge in Tennessee has ruled that Spotify will not be liable for any lost royalties, despite finding that Spotify did not have a license to stream the tracks.

The court also concluded that, if Spotify were to be found guilty of copyright infringement, any penalty would have to be paid by Kobalt Music Group, which collected royalties on behalf of Eminem’s publisher.

The case illustrates how confusing the business of administering music rights has become in the era of streaming.

Image source, Getty Images

When Eight Mile Style sued Spotify in 2019, it said the company had “acted deceptively” by pretending to have licenses for 243 Eminem songs, when it did not.

It further accused the company of making “random payments” for hits that had been streamed hundreds of millions of times, saying the money only accounted for “a fraction of those streams.

Intriguingly, Eminem was not a party to the lawsuit, only became aware of the legal action when it was filed.

The star’s music remained on Spotify throughout the five-year case. He is currently the 12th most-streamed artist on the platform, with 76 million monthly listeners.

‘Defies logic’

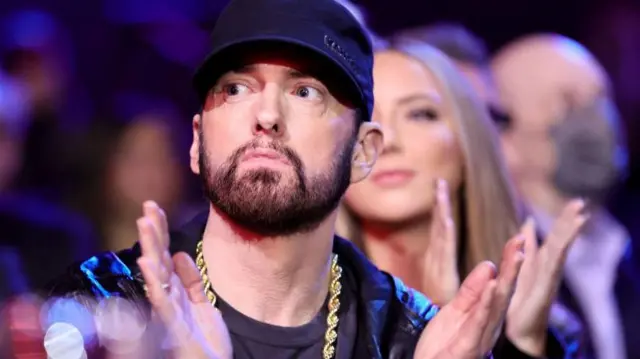

Spotify responded to the lawsuit in 2020 by blaming Kobalt Music Publishing, a company that administers the rights to hundreds of thousands of songs, as well as collecting royalties for rights-holders.

In court documents, Spotify alleged that Kobalt had misled it into believing it controlled the administration of Eight Mile’s catalogue, when that was not the case.

The company added that Eight Mile had “never once questioned” Spotify’s permission to stream Eminem’s songs, despite accepting royalty payments from the service since its US launch in 2011.

“Eight Mile instead suggests that it was somehow ‘duped’ by Spotify into thinking the compositions were properly licensed to explain away why it knowingly accepted and deposited royalty payments while remaining silent for years,” said the company’s lawyers.

“Eight Mile’s story defies logic.”

Eight Mile called those allegations “baseless”, and the case went back and forth for several years as their lawyers argued over the finer details of the case.

At one point, proceedings were delayed due to a dispute over whether Spotify’s CEO Daniel Ek would be deposed in the case.

Although the judge ruled that he would be forced to testify, the parties eventually asked for a summary judgment, so that the case would not have to go to a full trial.

Image source, Getty Images

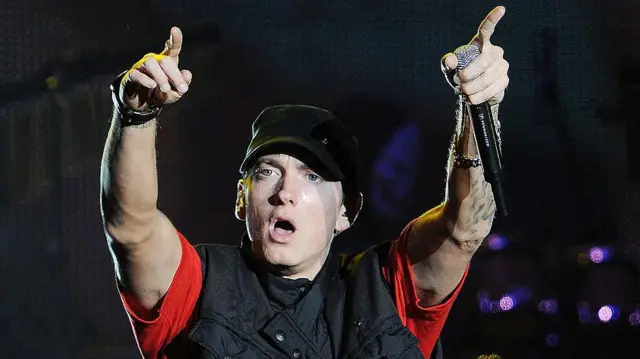

Judge Aleta A. Trauger published her opinion on 15 August, writing that Spotify should not be liable for any damages.

She highlighted that, although Kobalt was authorised to collect royalties for Eminem’s music, it was not authorised to licence the songs in the US and Canada.

Instead, those rights had been transferred in 2009 to company called Bridgeport Music, which is affiliated to Eight Mile itself.

However, the company “never formally notified any third party that it was taking over” the licensing of Eminem’s music, Judge Trauger wrote.

This situation was “inexplicable”, said the judge, unless it was a “strategic” attempt to extract money from Spotify by claiming copyright infringement.

Noting that the company had never sent Spotify “a single cease-and-desist letter”, she said that Eight Mile was not the “hapless victim” it claimed to be.

“Eight Mile Style, had every opportunity to set things right and simply chose not to do so for no apparent reason, other than that being the victim of infringement pays better than being an ordinary licensor,” she wrote.

The judge also noted that Spotify’s agreement with Kobalt did not include a database of the songs it could, and could not, stream.

“Kobalt’s primary stated reason for that approach is that the catalogue of a large administrator like Kobalt would be routinely changing, rendering any list almost immediately out of date,” she wrote.

That practice “makes it surprisingly plausible that Spotify might be genuinely confused, at times, regarding which rights it possessed and which it did not”.

However, one element of Spotify’s contract with Kobalt was clear: It protected the company against copyright claims on any works “administered” by Kobalt.

That means the company will have to pay any legal fees accrued over the last five years, which could be a large sum.