AFP

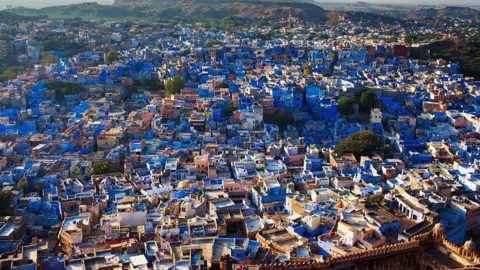

AFPFor years, the enchanting blue houses in the heart of an Indian city have drawn visitors from around the world. But the famed structures are slowly losing their charm – and colour, writer Arshia finds.

The neighbourhood of Brahmapuri in Jodhpur stands at the foot of a famous fort that’s perched atop a hill.

Built in 1459 by the Rajput king Rao Jodha – after whom the city is named – the walled, fortified settlement came up in the Mehrangarh Fort’s shadow, and was eventually recognised as the old or original city of Jodhpur, with azure-coloured homes.

Esther Christine Schmidt, assistant professor at Jindal School of Art and Architecture, says that the iconic blue colour likely wasn’t adopted before the 17th Century.

But since then, the area’s blue-coloured homes have become a distinct marker of Jodhpur’s identity.

In fact, Jodhpur, in Rajasthan state, is called the ‘Blue City’ because Brahmapuri remains its heart, despite expansions over the last 70 years, explains Sunayana Rathore, the curator of the Mehrangarh Museum.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBrahmapuri – which roughly translates to “the town of Brahmins” in Sanskrit – was built as a colony of upper-caste families who adopted the colour blue as a symbol of their sociocultural piety in the Hindu caste system.

They set themselves apart, much like the Jews of Chefchaouen – or the blue city of Morocco – who settled in the older part of town known as Medina, in the 15th Century, while fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. They are believed to have coloured their homes, mosques and even public offices in a rinse of blue, considered a divine hue in Judaism, signifying the holy skies.

Eventually, the colour proved to be beneficial in more ways than one. The blue paint mixed with limestone plaster – also used in the homes of Brahmapuri – cooled the interiors of the structures, besides bringing in tourists drawn by the neighbourhood’s striking appearance.

But unlike in Chefchaouen, the blue colour in Jodhpur has begun to fade. There are several reasons for this.

Historically, blue was a viable option for the residents of Brahmapuri because of the easy availability of natural indigo in the region – the town of Bayana in eastern Rajasthan was then one of the major indigo-producing centres in the country. But over the years, indigo fell out of favour because growing the crop damaged the soil excessively.

Tarun Sharma

Tarun SharmaMoreover, temperatures have risen so much now that the blue paint is not enough to keep the homes cool. An increase in disposable incomes has also led to a gradual shift to modern amenities like air conditioners that help people cope with the searing heat.

“Temperatures have risen gradually over the years,” says Udit Bhatia, assistant professor of civil engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Gandhinagar, who works on resilience infrastructure and the impacts of climatic extremes on built and natural systems.

A trend analysis done by IIT Gandhinagar showed that the average temperature of Jodhpur rose from 37.5C in the 1950s to 38.5C by 2016.

Apart from keeping houses cool, Mr Bhatia says the paint also had pest-repelling qualities as natural indigo was mixed with bright blue copper sulphate, a popular antifouling agent commonly used in paints from the 20th Century.

Tarun Sharma

Tarun SharmaWhile Mr Bhatia doesn’t think that urbanisation is evil, he points out that it can lead to the rather unscientific abandonment of traditions that were designed to serve systems and ecologies.

“Yesterday, if someone was walking down an alley in Jodhpur with blue homes on either side, and today they are walking down the same alley where the homes are now painted in a darker colour, even the lightest breeze will make them feel hotter than what they felt earlier,” he says.

It’s called the heat island effect, where the effect of rising temperatures is worsened when the heat and sunlight are amplified and reflected back into the environment by the concrete, cement and glass used to build structures. With darker paints, the impact is magnified further.

Moreover, with cities increasingly opening up to newer cultures and people, indigenous methods of building – like using lime plaster in hotter climes – are being replaced with newer techniques like using cement or concrete, which do not absorb the blue pigment well.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAditya Dave, a 29-year-old civil engineer from Brahmapuri, says that his 300-year-old family home has held on to blue for the most part, though, occasionally, they repaint the outer walls in other colours now.

That’s mainly because the scarcity of indigo has driven up costs in recent years. Repainting houses blue would cost around 5,000 rupees ($60; £45) up until a decade ago, while today, it would be more than 30,000 rupees.

“Today, there are also open drains lining homes which dirties the blue paint and damages the walls,” says Mr Dave.

That’s why when he built his own house in Brahmapuri five years ago, he chose a tile facade which doesn’t need to be refurbished frequently.

“It’s simply more cost-effective that way,” he says.

Tarun Sharma

Tarun SharmaBut this transformation leaves visitors feeling cheated, says Deepak Soni, a garments seller who works with local authorities to preserve the existing blue homes of Brahmapuri, and restore the ones that have abandoned the hue.

“We should feel embarrassed that when someone comes looking for the homes that formed the identity of our city, they don’t find them. So many foreigners compare Jodhpur to Chefchaouen. If Chefchaouen has managed to keep their homes blue for centuries, why can’t we?” he asks.

In 2018, Mr Soni, originally a resident of Brahmapuri who now lives beyond the walled part of Jodhpur, negotiated with local authorities and communities to save the unique heritage of their hometown. Since 2019, he has also raised funds locally from Brahmapuri residents to have the outer walls of 500 homes painted blue each year.

Tarun Sharma

Tarun SharmaOver the years, he has convinced nearly 3,000 homeowners in Brahmapuri to revert to blue for the outer walls and the roofs of their homes, “so that at least when someone takes a picture in Brahmapuri, the background appears blue”, he says.

Mr Soni estimates that about half of the roughly 33,000 homes in Brahmapuri are currently blue.

He is working with local officials and lawmakers on a plan to apply lime plaster, so more homes can be painted in the colour.

It’s the least he can do for the city he calls home, he says.

“Why will people from outside Jodhpur care about our city if we don’t care about its heritage, and do something to save it?”

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook