PA

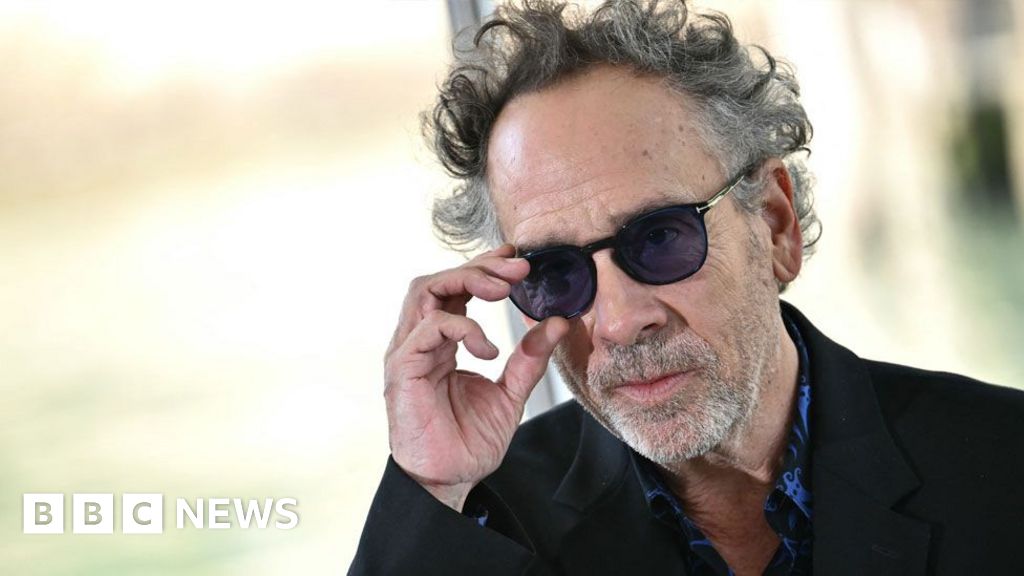

PADirector Tim Burton has revealed that being on the internet makes him feel “quite depressed”.

Ahead of the opening of a major career retrospective in London, he told BBC News: “Anybody who knows me knows I’m a bit of a technophobe.

“If I look at the internet, I found that I got quite depressed,” the 66-year-old said. “It scared me because I started to go down a dark hole. So I try to avoid it, because it doesn’t make me feel good.”

The World of Tim Burton at the Design Museum features 600 items which organisers say give “a rare private glimpse into his creative process” and goes on display in the UK for the first time on Friday.

Burton is best-known for directing films such as Batman, Edward Scissorhands, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and Alice in Wonderland, as well as Beetlejuice and its recent sequel.

Reflecting on his use of the internet, Burton said: “I get depressed very quickly, maybe more quickly than other people. But it doesn’t take me much to start to click and start to short circuit.”

The film-maker said keeping busy and doing simple things such as looking at clouds helps him feel better. As does his collection of ten giant dinosaur models that he keeps in his backyard including a 20ft T-Rex.

Burton pulls out his mobile phone and proudly shows us a picture of a 50-foot Brontosaurus. He buys the ones you find at amusement parks, adding that actor Nicolas Cage has “real ones”.

‘Humans were the ones who scared me’

Burton was born in a California suburb just outside of Los Angeles but has lived in London for the past 20 years.

“I was a foreigner in my own country,” he told the BBC when asked about adopting the UK capital. When I came here, even as a foreigner, I felt more at home, because that’s where I feel comfortable.

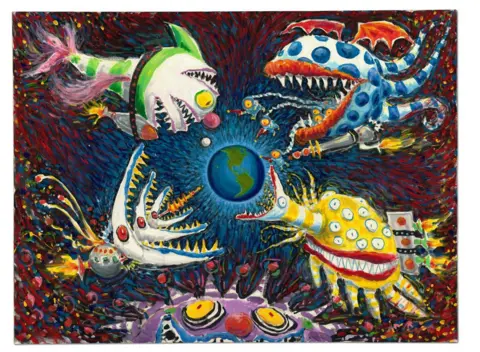

Burton has long been considered a “tortured outcast” and self-declared “weirdo”. As a child, he channelled his creativity into art and grew up watching classic horror movies and creature features which developed his love for monsters.

“It was very clear from King Kong to Frankenstein to Creature from the Black Lagoon that all the monsters were the most emotional. The humans were the ones that scared me,” he said.

“They were the angry villagers in Frankenstein – like the internet – these nameless faces [Burton makes monster roaring noises] and the monster always had the most emotion and most feeling even though they’re looked upon as a certain way.

“Every monster usually has some kind of pathos and some kind of humanity” that the humans lacked he added.

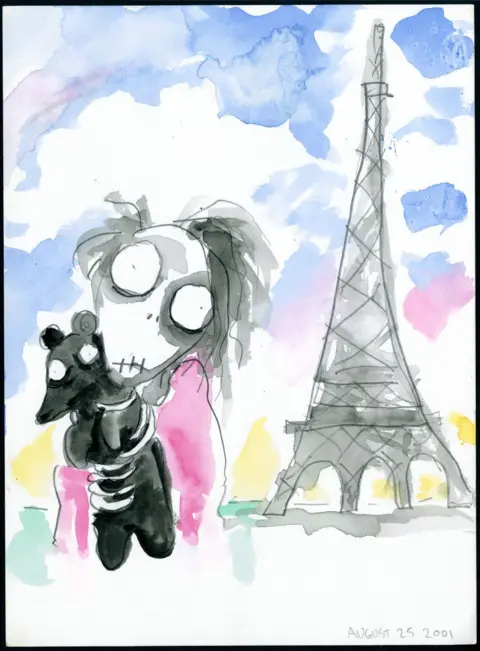

Objects connected to films ranging from Catwoman to Corpse Bride have been loaned to the new exhibition from Burton’s personal archives, film studios, and private collections of collaborators such as the designer Colleen Atwood.

Tim Burton/20th Century Studios

Tim Burton/20th Century Studios Tim Burton

Tim BurtonWhat still scares Burton are the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence.

“It’s something I can’t even quite fathom,” he said, before referring to an incident last year where AI was used to transform Disney characters into Burton-style characters.

“Until it happens to you, really don’t understand it. But it was quite disturbing: intellectually and emotionally disturbing. It felt like my soul had been taken from me.

“It’s like when other cultures say, ‘oh, don’t take my picture, because you’re taking away my soul’. And that’s how it is. It’s something that’s robbing you of humanity.

“All I can say is, like, I understand these other cultures when they feel like your soul is being sucked”.

No more Batman for Burton

Burton first began working as an apprentice animator at Disney and made immense contributions to stop-motion animation before going on to direct blockbusters such as Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992).

When asked whether he would return to directing a film from the superhero genre, his response was a quick “no”.

“It felt new at the time,” he reflects. “There was pressure because it was a big movie and it was a different interpretation of comic books. So that was a pressure, but it wasn’t the pressure that you would experience now.”

Burton demurs when asked about what he wants to shoot next. Perhaps the horror classic Frankenstein?

“No, no,” he laughs. “I’ve done my version with a dog [referring to his 2012 film Frankenweenie]. That’s fine.”

He admits to feeling invigorated with recent successes of Beetlejuice Beetlejuice and the Netflix series Wednesday, of which he directed four episodes.

“The Hollywood journey is an Alice in Wonderland kind of journey. You go up, you go down, you go sideways. That’s the way it is,” he said.

“What I realize now, maybe because I’m older as well, is OK I’m just gonna do what I want. And if you want to do it, fine. If not, then you don’t have to go on this journey with me”.

MGM Television Entertainment

MGM Television EntertainmentMore than 32,000 people bought advance tickets to The World of Tim Burton, making this the biggest ever ticket pre-sale in the Design Museum’s 35-year history.

The exhibition has been staged in 14 cities in 11 countries since 2014. But the London version displays more than 90 items that are new.

Visitors will also be able to see a recreation of Burton’s private studio which includes a miniature version of Godzilla on his work desk, reflecting his love of Japanese Kaiju films.

But Burton had initially resisted allowing the exhibition to come to London.

“It’s a strange thing, to put 50 years of art and your life on view for everyone to see,” he said.

“However, collaborating with the Design Museum for this final stop was the right choice. They understand the art”.

Tim Burton

Tim BurtonTim Marlow, CEO of the Design Museum, said: “During his extraordinary career, Tim Burton has harnessed a compelling mixture of gothic horror and black comedy, of melancholy and enchantment, of oddball whimsy and visionary range in the creation of fantastical filmic worlds.”

However when discussing his success, Burton tells us that he rejects the term “Burtonesque” even though it’s widely used in popular culture to describe his oeuvre.

“I never liked that,” he says firmly. “I don’t want to become a thing. It’s taken me my whole life to try to be something like resembling human”.

The World of Tim Burton runs from 25 October 2024 – 21 April 2025 at the Design Museum in London.